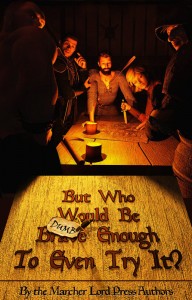

Time for “Speculative Story Saturday” here at Marcher Lord Press! Here is the latest installment.

Time for “Speculative Story Saturday” here at Marcher Lord Press! Here is the latest installment.

There are times when it’s best to conceal oneself in plain sight. I am Cludge, or so it’s thought.

My given name is Cornelius Fander Tillian, prefect of the mountain baronies that lie hidden above Atzapar valley and the land of Celis. We are the eyes of the world, long assumed to have passed away with the last Great Age. We are the rumble at the mountaintop, the strange fire by night at the roof of the world, the unseen, though we reside in plain view of all in Celis. We are the keepers of the tenth ray.

The thing was easily done, as men by nature deceive themselves. After a minor indiscretion—of which I will not disclose further—my masters sentenced me to patrol the hinterlands where I was to attach myself to the notorious thief Tekla in anticipation of a quest, the likes of which, although unknown to its participants, has not been equaled in gravity or consequence since the last age. It’s typical: they perceive me as the half-witted brute, and I’m the only one who has a grasp of the full danger beyond the Dank Wood.

Back in the baronies, we are wispy creatures, beautiful amalgamations of wind, water, and light, skilled in elemental arts and custodians of skyward wisdom. None of which we may descend the mountains with, save to appear as the icicles on your eaves in winter or as the dew of your lawn on sultry summer mornings. As such, we are a soft voice in the minds of men, unknown to them, but speaking an understanding long since ignored.

They transformed me into the brute Cludge. As repulsive as half-giants are, I was fortunate to receive this form. Some of my fellows have been sentenced to their terms in the lowlands as wood rats, trolls, and even sludge feeders. I suspect this may be on account of the dire importance of our quest. For the entire term of my sentence, I’m a seven-foot colossus with the strength of five men.

I’ll carry my burden, but I long to return to the mountains.

Tekla imagined it was the Flow that led me to her. I played well with her and thus entered Barzallai’s quest assembly attached to her coattails, unnoticed. A few grunts, coupled with well-timed monosyllabic utterances and a feigned allegiance to Tekla, was all it took. I hide in plain sight.

Barzallai was simple: Cludge count four, I had said. His condescension in reply was palpable.

I managed to fool Abelard—he was the one who might be able to smoke me out since he is a priest-mage of the Church itinerant—with boorishness. The ear-picking and subsequent inspecting of wax (I didn’t even need to pick my nose) accomplished that, along with enthusiasm for rat and spider meat.

That’s the worst part of this: the baseness of earth, far below my mountain home. The air is wrong, somehow. It’s heavy. The earth clings to you like an orphan child, God bless it. Yet, I will be faithful to my masters and eat spider for now.

After the spider ordeal, which the effects thereof now languished unsettled in my belly, the camp relaxed, each of us loosely connected—more like arms of a starfish rather than five fingers of the same hand. They were full of human frailty: cocksure in themselves and their singular abilities. Myopic in their understanding of things, save perhaps for Abelard. They saw but a piece of the world—their own, and all revolved around their particular slice of reality. I, the idiot, the cludge, saw it in them.

In the wee hours, we reclined around the waning fire. Barzallai slept with his head perched on his quiver. Abelard and Raibert were pitched against a sizeable log. Tekla lay stretched out between the roots of an oak.

I had managed to separate myself from the group—they separated from me, more accurately— by virtue of some well-timed spider-and-rat-belch combos and a strategic spray of stout ogre-ish crepitation. It’s a simple and well-utilized maneuver common to half-giants.

I waited for the crew to fall asleep, feigning it myself until they did. For in their sleep, I knew their dreams would come, and we of the mountain baronies are dream watchers.

Tekla’s emerged first, as it was the most rudimentary. It exited from her closed eyelids, seeping out from the corners of her eyes like gas infused with light. Hers was orange, the color of a deep sunset, tinged with a ruddy border. Above her floated a stack of gold, lopsided against the oak she slept under, as if it had ruptured from the trunk of the tree and spilled onto the ground.

At first I didn’t notice her until I spied her eyes from within the pile of gold. They darted back and forth between her companions in mistrust. A knife lay concealed and poised, ready to strike. A time or two, her eyes even found me with the same suspicion. It hurt a little, I admit. But of course I am the deceiver in our relationship.

Barzallai’s dream emerged next. For a moment I kidded myself that his heart was pure; his dream was a lush countryside, reminiscent of the finer pastoral regions of Atzapar valley. A wandering stream dotted with stately oaks cut through cliffs of onyx rock. It floated above him as vivid and pure as the primordial garden of God’s creation.

But in the garden appeared Tekla with her withering glare, which Barzallai seemed to relish. The dream turned deep crimson with lust, and Barzallai cried out over and over heaven help me. It seemed to me a half-hearted cry.

Raibert slept sound. I witnessed no dream from him. Odd. I would have to keep a closer eye on him in the nights to come. But Abelard. There was a tormented but exalted soul.

His dream ephemera exited from his mouth instead of his eyes. It glittered as diamond dust in the night sky as it rose, ground finer than any substance I had ever seen. It floated above him in the shape of the cross, and somehow the priest-mage managed to carry it and prostrate himself in front of it at the same time. He wailed that he was both unfit and unable for the task that lay ahead of him. He was right, of course, but seemed to draw an inner strength from that realization.

Raibert exhaled audibly, rolled over, and began to snore, as if released from a protective spell and into genuine sleep. Then the dreams faded at once from my companions. I knew what that meant: it was now time to face my own dream.

The vision came as the charge of horsemen. The forest flared, as if a thousand torches were lit at once, and my body went stiff in paralysis—one so strong even a cludge could not break free of it.

The forest melted away, and in its place the vision stampeded toward me. It was the fortress of Landgrave Christoph, its lone spire reaching to the sky. Inside its gates, the souls of all Celis writhed in agony as if the fortress were a fiery cauldron of blood. Their screams pierced my heart. Their wails drifted into a void, for the fortress was all that was, and outside its walls was nothingness. I longed to cover my ears, but my arms would not respond.

I was left to witness their infernal end, an unending doom under the gaze of evil emanating from the very crystal we were pledged to in our quest. Indeed, I saw my companions there as well, naked and in despair, for nothing could stand in the light of the crystal. For the first time, I genuinely felt for them.

Our mission must not fail or Celis would fall.

The dream evaporated, and mobility returned to my limbs. I fought the urge to flee to the mountains, to leave this heavy, earthy world that clung to me. This sin-laden realm, one that was in mortal peril.

Instead, I noticed Abelard studying me behind half-closed eyelids. I picked my nose. Half-giants are blessed with rather large olfactory systems, and I held my gleanings out for all to see. Abelard rolled over, satisfied, I was sure, that I was Cludge.

Hidden in plain sight.

Way cool! Nice turn of events, Marc.

Way cool! Nice turn of events, Marc.

Love it!

Love it!

Nice, Marc!

Nice, Marc!

Excellent stuff, O thou who is not Quixote.

Excellent stuff, O thou who is not Quixote.

As the name might suggest, Quixote is more versed in fantasy than I, if he can properly be said to be versed in anything other than arguing, although I have noticed he excels at the villain’s monologue and generally in making sport of himself. Well, he’s somewhat of a dog-whisperer as well, and he did memorize John 11:35 in both the KJV and NIV translations. This was my first attempt at fantasy–yes, I’m a newb (alternate spelling noob) and not versed at all in it–so thank you all for the encouragement. Looking ahead to episode 6…

As the name might suggest, Quixote is more versed in fantasy than I, if he can properly be said to be versed in anything other than arguing, although I have noticed he excels at the villain’s monologue and generally in making sport of himself. Well, he’s somewhat of a dog-whisperer as well, and he did memorize John 11:35 in both the KJV and NIV translations. This was my first attempt at fantasy–yes, I’m a newb (alternate spelling noob) and not versed at all in it–so thank you all for the encouragement. Looking ahead to episode 6…

“if he can properly be said to be versed in anything other than arguing”

Hmm, indeed…although in his defense he usually argues graciously and impeccably.

“although I have noticed he excels at the villain’s monologue and generally in making sport of himself.”

Which is, of course, as it should be. He *does* have that funny accent, after all.

“if he can properly be said to be versed in anything other than arguing”

Hmm, indeed…although in his defense he usually argues graciously and impeccably.

“although I have noticed he excels at the villain’s monologue and generally in making sport of himself.”

Which is, of course, as it should be. He *does* have that funny accent, after all.